60 Classic Australian Poems for Children Read online

Page 6

On the Night Train

Henry Lawson

Have you seen the bush by moonlight, from the train, go running by?

Blackened log and stump and sapling, ghostly trees all dead and dry;

Here a patch of glassy water; there a glimpse of mystic sky?

Have you heard the still voice calling—yet so warm, and yet so cold:—

‘I’m the Mother-Bush that bore you! Come to me when you are old’?

Did you see the Bush below you sweeping darkly to the range,

All unchanged and all unchanging, yet so very old and strange!

While you thought in softened anger of the things that did estrange?—

(Did you hear the Bush a-calling, when your heart was young and bold:—

‘I’m the Mother-bush that nursed you; Come to me when you are old’?)

In the cutting or the tunnel, out of sight of stock or shed,

Did you hear the grey Bush calling from the pine-ridge overhead:—

‘You have seen the seas and cities—all is cold to you, or dead—

All seems done and all seems told, but the grey-light turns to gold!

I’m the Mother-Bush that loves you—Come to me now you are old’?

Birth, A Little Journal of Australian Poetry, 1922

31

‘Ough!’

WT Goodge

(A fonetic fansy, dedicated to Androo Karnegee, the millionaire spelling reformer.)

The baker-man was kneading dough

And whistling softly, sweet and lough.

Yet ever and anon he’d cough

As though his head were coming ough!

‘My word!’ said he, ‘but this is rough;

This flour is simply awful stough!’

He punched and thumped it through and through,

As all good bakers always dough!

‘I’d sooner drive,’ said he, ‘a plough

Than be a baker, anyhough!’

Thus spake the baker kneading dough;

But don’t let on I told you sough!

The Bulletin, 1906

32

The Pieman

CJ Dennis

I’d like to be a pieman, and ring a little bell,

Calling out, ‘Hot pies! Hot pies to sell!’

Apple-pies and Meat-pies, Cherry-pies as well,

Lots and lots and lots of pies—more than you can tell.

Big, rich Pork-pies! Oh, the lovely smell!

But I wouldn’t be a pie-man if …

I wasn’t very well.

Would you?

A Book for Kids, 1921

33

Pioneers

Frank Hudson

We are the old-world people,

Ours were the hearts to dare;

But our youth is spent, and our backs are bent,

And the snow is on our hair.

Back in the early fifties,

Dim through the mist of years,

By the bush-grown strand of a wild strange land

We entered—the Pioneers.

Our axes rang in the woodlands,

Where the gaudy bush-birds flew,

And we turned the loam of our new-found home,

Where the eucalyptus grew.

Housed in the rough log shanty,

Camped in the leaking tent,

From sea to view of the mountains blue,

Where the eager fossickers went.

We wrought with a will unceasing,

We moulded, and fashioned, and planned,

And we fought with the black, and we blazed the track,

That ye might inherit the land.

Here are your shops and churches,

Your cities of stucco and smoke;

And the swift trains fly, where the wild-cat’s cry

Once the sad bush silence broke.

Take now the fruit of our labour,

Nourish and guard it with care,

For our youth is spent, and our backs are bent.

And the snow is on our hair.

The Song of Manly Men and other verses, 1908

34

Pioneers

Banjo Paterson

They came of bold and roving stock that would not fixed abide;

They were the sons of field and flock since e’er they learnt to ride,

We may not hope to see such men in these degenerate years

As those explorers of the bush—the brave old pioneers.

’Twas they that rode the trackless bush in heat and storm and drought;

’Twas they that heard the master-word that called them farther out;

’Twas they that followed up the trail the mountain cattle made,

And pressed across the mighty range where now their bones are laid.

But now the times are dull and slow, the brave old days are dead

When hardy bushmen started out, and forced their way ahead

By tangled scrub and forests grim towards the unknown west,

And spied the far-off promised land from off the ranges’ crest.

Oh! ye, that sleep in lonely graves by far-off ridge and plain,

We drink to you in silence now as Christmas comes again,

The men who fought the wilderness through rough unsettled years—

The founders of our nation’s life, the brave old pioneers.

Australian Town and Country Journal, 1896

35

Pitchin’ at the Church

PJ Hartigan (John O’Brien)

On the Sunday morning mustered,

Yarning at our ease;

Buggies, traps and jinkers clustered

Underneath the trees,

Horses tethered to the fences;

Thus we hold our conferences

Waiting till the priest commences—

Pitchin’ at the Church.

Sheltering in the summer’s shining

Where the shadows fall;

When the winter’s sun is pining,

Lined along the wall;

Yarning, reckoning, ruminating,

‘Yeos’ and lambs and wool debating,

Squatting, smoking, idly waiting—

Pitchin’ at the Church.

Young bloods gathered from the others

Tell their dreamings o’er;

Beaded-bonneted old mothers

Grouped around the door;

Dainty bush girls, trim and fairy,

All that’s neat and sweet and airy—

Nell, and Kate, and Laughing Mary—

Pitchin’ at the Church.

Up comes someone briskly driving,

‘Cutting matters fine’:

All his ‘fam’ly lot’ arriving

Wander in a line

Off in some precise direction,

Till they find their proper section,

Greet it with an interjection—

Pitchin’ at the Church.

‘Mornun’, Jack.’ ‘Good-mornun’, Martin.’

‘Keepin’ pretty dry!’

‘When d’you think you’ll finish cartin’?’

‘Prices ain’t too high?’

Round about the yarnin’ strayin’—

Dances, sickness—frocks surveyin’—

Wheat is ‘growed,’ the ‘hens is layin”—

Pitchin’ at the Church.

Around the Boree Log and other verses, 1922

36

Poets

CJ Dennis

Each poet that I know (he said)

Has something funny in his head,

Some wandering growth or queer disease

That gives to him a strange unease.

If such a thing he hasn’t got

What makes him write his silly rot?

All poets’ brains, so I have found,

Go, like the music, round and round.

Why they are suffered e’er to tread

This sane man’s earth seems strange (he said).

I’ve never met a poet

yet,

A rhymster I have never met

Who could talk sense like any man—

Like I, or even you, say, can.

They make me sick! The time seems ripe

To clean them up and all their tripe.

And yet (He stopped and felt his head)

I met a poet once (he said)

Who, when I said he made me sick

Hit me a punch like a mule’s kick.

That only goes to prove again

The theory that I maintain:

A man who can’t gauge that crazy bunch;

No poet ought to pack a punch.

Of all the poetry I’ve read

I’ve never yet seen one (he said)

That couldn’t be, far as it goes,

Much better written out in prose.

It’s what they eat, I often think;

Or, yet more likely, what they drink.

Aw, poets! All the tribe, by heck,

Give me a swift pain in the neck.

The Herald, 1936

37

Post-Hole Mick

GM Smith (Steele Grey)

A short time back while over in Vic.

I met with a chap called Post-Hole Mick;

He was a raw-boned, loose-built son of a paddy

And at putting down post-holes he was the daddy.

And wherever you’d meet him, near or far,

He had always his long-handled shovel and bar,

I suppose you all know what I mean by a bar,

It’s a lump of wrought-iron the shape of a spar.

With one chisel end for digging the ground

And average weight about twenty pound;

Mick worked for the cockies around Geelong,

For a time they kept him going strong.

He would sink them a hundred holes for a bob,

And, of course, soon worked himself out of a job.

But when post-hole sinking got scarce for Mick,

He greased his brogues and cut his stick.

And one fine day he left Geelong

And took his shovel and bar along.

He took to the track in search of work,

And struck due north, enroute to Bourke.

It seems he had been some time on tramp

When one day he struck a fencers’ camp.

The contractor there was wanting a hand,

As post-hole sinkers were in demand.

He showed him the line and put him on,

But while he looked round, shure Mick was gone.

There were the holes, but where was the man?

Then his eye along the line he ran.

He’d already put down about ninety-nine,

And at the rate of a hunt he was running the line.

He had a few sinkers he thought was quick

Till the day he engaged with Post-Hole Mick.

When he finished his contract he started forth,

And it appears kept on his course due north;

For I saw a report in the Croydon Star

Where a fellow had passed with a shovel and bar.

To give you an idea of how he could walk

A day or two later he struck Cape York.

If they can’t find him work there putting down holes

I’m afraid he’ll arrive at one of the poles.

The Days of Cobb & Co. and other verses, 1906

38

The Roaring Days

Henry Lawson

The night too quickly passes

And we are growing old,

So let us fill our glasses

And toast the Days of Gold:

When finds of wond’rous treasure

Set all the South ablaze,

And you and I were faithful mates

All through the roarin’ days!

Then stately ships came sailing

From ev’ry harbour’s mouth,

And sought the land of promise

That beaconed in the South;

Then southward streamed their streamers

And swelled their canvas full

To speed the wildest dreamers

E’er borne in vessel’s hull!

And ’neath the sunny dadoes,

Against the lower skies,

The shining Eldoradoes,

Forever would arise;

And all the bush awakened,

Was stirred in wild unrest,

And all the year a human stream

Went pouring to the West. 3

The rough bush roads re-echoed

The bar-room’s noisy din,

When troops of stalwart horsemen

Dismounted at the inn.

And oft the hearty greetings

And hearty clasp of hands,

Would tell of sudden meetings

Of friends from other lands;

When, puzzled long, the new-chum

Would recognise at last,

Behind a bronzed and bearded skin,

A comrade of the past.

And when the cheery camp-fire

Suffused the bush with gleams,

The camping-grounds were crowded

With caravans of teams;

Then home the jests were driven,

And good old songs were sung,

And choruses were given,

The strength of heart and lung.

Oh, they were lion-hearted

Who gave our country birth!

Oh, they were of the stoutest sons

From all the lands on earth!

Oft when the camps were dreaming,

And fires began to pale,

Then thro’ the ranges gleaming

Would come the Royal Mail.

Then, drawn by foaming horses,

And lit by flashing lamps,

Old ‘Cobb and Co.’s,’ in Royal State,

Went dashing past the camps.

Oh, who would paint a gold-field,

And limn the scene aright,

As we have often seen it

In early morning’s light;

The yellow mounds of mullock

With spots of red and white,

The scattered quartz that glistened

Like diamonds in light;

The azure line of ridges,

The bush of darkest green,

The little homes of calico

That dotted all the scene.

I hear the fall of timber

From distant flats and fells,

The pealing of the anvils

As clear as little bells,

The rattle of the cradle,

The clack of windlass-boles,

The flutter of the crimson flags

Above the golden holes.

Ah, then our hearts were bolder,

And if our fortune frowned

Our swags we’d lightly shoulder

And tramp to other ground.

But golden days are vanished,

And altered is the scene;

The diggings are deserted

The camping-grounds are green.

The flaunting flag of progress

Is in the West unfurled,

The mighty bush with iron rails

Is tethered to the world.

Their shining Eldorado,

Beneath the southern skies,

Was day and night for ever

Before their eager eyes.

The brooding bush, awakened,

Was stirred in wild unrest,

And all the year a human stream

Went pouring to the West.

The Bulletin (Christmas edition), 1889

39

A Ruined Reversolet

CJ Dennis

’Tis Spring!

Sing Hey!

Birds sing

All day.

In trees

Bees hum—

I’ sneeze—

Skatch-Humb!!

I sdeeze.

Bees hub.

Id tree

s

All day

Birds sig.

Sig Hey! ’Tis Sprig!

The Bulletin, 1908

40

Said Hanrahan

PJ Hartigan (John O’Brien)

‘We’ll all be rooned,’ said Hanrahan,

In accents most forlorn,

Outside the church, ere Mass began,

One frosty Sunday morn.

The congregation stood about,

Coat-collars to the ears,

And talked of stock, and crops, and drought,

As it had done for years.

‘It’s lookin’ crook,’ said Daniel Croke;

‘Bedad, it’s cruke, me lad,

For never since the banks went broke

Has seasons been so bad.’

‘It’s dry, all right,’ said young O’Neil,

With which astute remark

He squatted down upon his heel

And chewed a piece of bark.

And so around the chorus ran

‘It’s keepin’ dry, no doubt.’

‘We’ll all be rooned,’ said Hanrahan,

‘Before the year is out.’

‘The crops are done; ye’ll have your work

To save one bag of grain;

From here way out to Back-o’-Bourke

They’re singin’ out for rain.

‘They’re singin’ out for rain,’ he said,

‘And all the tanks are dry.’

The congregation scratched its head,

And gazed around the sky.

‘There won’t be grass, in any case,

Enough to feed an ass;

There’s not a blade on Casey’s place

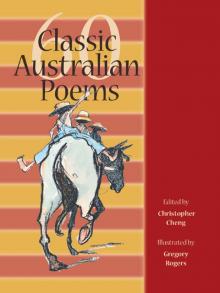

60 Classic Australian Poems for Children

60 Classic Australian Poems for Children