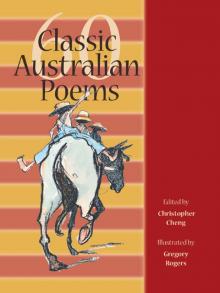

60 Classic Australian Poems for Children Read online

Page 5

The sort that are by mountain horsemen prized.

He was hard and tough and wiry—just the sort that won’t say die;

There was courage in his quick impatient tread,

And he bore the badge of gameness in his bright and fiery eye,

And the proud and lofty carriage of his head.

But still so slight and weedy one would doubt his power to stay,

And the old man said, ‘That horse will never do

For a long and tiring gallop—lad, you’d better stop away,

The hills are far too rough for such as you.’

So he waited sad and wistful; only Clancy stood his friend.

‘I think we ought to let him come,’ he said;

‘I warrant he’ll be with us when he’s wanted at the end,

For both his horse and he are mountain bred.

‘He hails from Snowy River, up by Kosciusko’s side,

Where the hills are twice as steep and twice as rough—

Where a horse’s hoofs strike firelight from the flint stones every stride,

The man that holds his own is good enough.

And the Snowy River riders on the mountains make their home,

Where the river runs those giant hills between.

I have seen full many horsemen since I first commenced to roam,

But never yet such horsemen have I seen.’

So he went; they found the horses by the big Mimosa clump;

They raced away towards the mountain’s brow,

And the old man gave his orders, ‘Boys, go at them from the jump,

No use to try for fancy-riding now;

And, Clancy, you must wheel them—try and wheel them to the right.

Ride boldly, lad, and never fear the spills,

For never yet was rider that could keep the mob in sight,

If once they gain the shelter of those hills.’

So Clancy rode to wheel them—he was racing on the wing

Where the best and boldest riders take their place—

And he raced his stock-horse past them, and he made the ranges ring

With the stockwhip, as he met them face to face,

And they wavered for a moment while he swung the dreaded lash,

But they saw their well-loved mountain full in view,

And they charged beneath the stockwhip with a sharp and sudden dash,

And off into the mountain-scrub they flew.

Then fast the horsemen followed where the gorges deep and black

Resounded to the thunder of their tread,

And the stockwhips woke the echoes, and they fiercely answered back

From cliffs and crags that beetled overhead;

And upward, upward ever, the wild horses held their way

Where mountain-ash and kurrajong grew wide.

And the old man muttered fiercely: ‘We may bid the mob good-day,

No man can hold them down the other side.’

When they reached the mountain’s summit even Clancy took a pull—

It well might make the boldest hold their breath,

The wild hop-scrub grew thickly and the hidden ground was full

Of wombat-holes, and any slip was death;

But the man from Snowy River let his pony have his head,

And he swung his stockwhip round and gave a cheer,

And he raced him down the mountain like a torrent down its bed,

While the others stood and watched in very fear.

He sent the flint-stones flying, but the pony kept his feet;

He cleared the fallen timber in his stride,

And the man from Snowy River never shifted in his seat—

It was grand to see that mountain horseman ride

Through stringy barks and saplings on the rough and broken ground,

Down the hillside at a racing-pace he went,

And he never drew the bridle till he landed safe and sound

At the bottom of that terrible descent.

He was right among the horses as they climbed the further hill,

And the watchers, on the mountain standing mute,

Saw him ply the stockwhip fiercely—he was right among them still

As he raced across the clearing in pursuit;

Then they lost him for a moment where the mountain gullies met

In the ranges—but a final glimpse reveals

On a dim and distant hillside the wild horses racing yet

With the man from Snowy River at their heels.

And he ran them single-handed till their sides were white with foam.

He followed like a bloodhound on their track

Till they halted, cowed and beaten—then he turned their heads for home,

And alone and unassisted brought them back;

And his hardy mountain pony—he could scarcely raise a trot—

He was blood from hip to shoulder from the spur,

But his pluck was still undaunted and his courage fiery hot,

For never yet was mountain horse a cur.

And down by Araluen, where the stony ridges raise

Their torn and rugged battlements on high,

Where the air is clear as crystal and the white stars fairly blaze

At midnight in the cold and frosty sky,

And where, around ‘the Overflow,’ the reedbeds sweep and sway

To the breezes and the rolling plains are wide,

The man from Snowy River is a household word to-day,

And the stockmen tell the story of his ride.

The Bulletin, 1890

* * *

Have a close look at the front of the current Australian $10 note.

Can you see:

• an extract from this poem written in Paterson’s own handwriting?

• an illustration inspired by this poem? It was based on lithographs and photographs printed in 1870s newspapers.

In the last verse there is often a different first line:

And down by Araluen, where the stony ridges raise becomes

And down by Kosciusko, where the pine-clad ridges raise

* * *

24

Mr Smith

DH Souter

MR SMITH OF TALLABUNG

HAS VERY WICKED WAYS,

HE WANDERS OFF INTO THE BUSH

AND STAYS AWAY FOR DAYS

He never says he’s going;

We only know he’s gone.

There’s lots of cats like Mr Smith,

Who like to walk alone.

He plays that he’s a tiger,

And makes the dingoes run.

He scratches emus on the legs

And plays at football with their eggs;

But does it all in fun.

And then one day, he’s home again,

The skin all off his nose;

His ears all torn and tattered,

His face all bruised and battered,

And bindies in his toes.

He wanders round and finds a place

To sleep in in the sun.

And dream of all the wicked things

That he has been and done.

MR SMITH OF TALLABUNG

MAY BE A BAD CAT;

BUT EVERYBODY LIKES HIM—

SO THAT’S JUST THAT.

Bush-Babs: with pictures, 1933

* * *

Bush-Babs: with pictures is Souter’s collection of nursery rhymes (Souter called them jingles), some of which he wrote and illustrated for his children. It was published in 1933. The ‘Souter cat’ is there along with a sketch of DH Souter himself in the introduction. Cats also feature on chairs he owned, in sketches and on his chinaware.

* * *

25

Mulga Bill’s Bicycle

Banjo Paterson

’Twas Mulga Bill, from Eaglehawk, that caught the cycling craze.

He turned away the good old horse that served him many days.

He dressed himself in cycling clothes

, resplendent to be seen.

He hurried off to town and bought a shining new machine;

And as he wheeled it through the door, with air of lordly pride,

The grinning shop assistant said, ‘Excuse me, can you ride?’

‘See here, young man,’ said Mulga Bill, ‘from Walgett to the sea,

From Conroy’s Gap to Castlereagh, there’s none can ride like me.

I’m good all round at everything, as everybody knows,

Although I’m not the one to talk—I hate a man that blows.

‘But riding is my special gift, my chiefest, sole delight;

Just ask a wild duck can it swim, a wild cat can it fight.

There’s nothing clothed in hair or hide, or built of flesh or steel,

There’s nothing walks or jumps, or runs, on axle, hoof, or wheel,

But what I’ll sit, while hide will hold and girths and straps are tight.

I’ll ride this here two-wheeled concern right straight away at sight.’

’Twas Mulga Bill, from Eaglehawk, that sought his own abode,

That perched above the Dead Man’s Creek, beside the mountain road.

He turned the cycle down the hill and mounted for the fray,

But ere he’d gone a dozen yards it bolted clean away.

It left the track, and through the trees, just like a silver streak,

It whistled down the awful slope towards the Dead Man’s Creek.

It shaved a stump by half an inch, it dodged a big white-box:

The very wallaroos in fright went scrambling up the rocks,

The wombats hiding in their caves dug deeper underground,

As Mulga Bill, as white as chalk, sat tight to every bound.

It struck a stone and gave a spring that cleared a fallen tree.

It raced beside a precipice as close as close could be;

And then as Mulga Bill let out one last despairing shriek

It made a leap of 20 feet into the Dead Man’s Creek.

’Twas Mulga Bill, from Eaglehawk, that slowly swam ashore:

He said, ‘I’ve had some narrer shaves and lively rides before;

I’ve rode a wild bull round a yard to win a five-pound bet,

But this was the most awful ride that I’ve

encountered yet.

I’ll give that two-wheeled outlaw best; it’s

shaken all my nerve

To feel it whistle through the air and plunge and buck and swerve

It’s safe at rest in Dead

Man’s Creek, we’ll

leave it lying still;

A horse’s back is good

enough henceforth for Mulga Bill.’

The Sydney Mail, 1896

26

My Typewriter

Edward Dyson

I have a trim typewriter now,

They tell me none is better;

It makes a pleasing, rhythmic row,

And neat is every letter.

I tick out stories by machine,

Dig pars, and gags, and verses keen,

And lathe them off in manner slick.

It is so easy, and it’s quick.

And yet it falls short, I’m afraid,

Of giving satisfaction,

This making literature by aid

Of scientific traction;

For often, I can’t fail to see,

The dashed thing runs away with me.

It bolts, and do whate’er I may

I cannot hold the runaway.

It is not fitted with a brake,

And endless are my verses,

Nor any yarn I start to make

Appropriately terse is.

’Tis plain that this machine-made screed

Is fit but for machines to read;

So ‘Wanted’ (as an iron censor)

‘A good, sound, secondhand condenser!’

The Bulletin, 1917

27

Native Companions Dancing

John Shaw Neilson

On the blue plains in wintry days

These stately birds move in the dance.

Keen eyes have they, and quaint old ways

On the blue plains in wintry days.

The Wind, their unseen Piper, plays,

They strut, salute, retreat, advance;

On the blue plains, in wintry days,

These stately birds move in the dance.

Collected Poems of John Shaw Neilson, 1934

28

Old Granny Sullivan

John Shaw Neilson

A pleasant shady place it is, a pleasant place and cool—

The township folk go up and down, the children pass to school.

Along the river lies my world, a dear sweet world to me:

I sit and learn—I cannot go; there is so much to see.

But Granny, she has seen the world, and often by her side

I sit and listen while she speaks of youthful days of pride;

Old Granny’s hands are clasped; she wears her favourite faded shawl—

I ask her this, I ask her that: she says, ‘I mind them all.’

The boys and girls that Granny knew, far o’er the seas are they;

But there’s no love like the old love, and the old world far away;

Her talk is all of wakes and fairs—or how, when night would fall,

‘’Twas many a quare thing crept and came!’ and Granny ‘minds them all.’

A strange new land was this to her, and perilous, rude and wild—

Where loneliness and tears and care came to each mother’s child:

The wilderness closed all around, grim as a prison wall;

But white folk then were stout of heart—ah! Granny ‘minds it all.’

The day she first met Sullivan—she tells it all to me—

How she was hardly twenty-one, and he was twenty-three.

The courting days! the kissing days!—but bitter things befall

The bravest hearts that plan and dream. Old Granny ‘minds it all.’

Her wedding-dress I know by heart: yes! every flounce and frill;

And the little home they lived in first, with the garden on the hill.

’Twas there her baby boy was born, and neighbours came to call,

But none had seen a boy like Jim—and Granny ‘minds it all.’

They had their fight in those old days; but Sullivan was strong,

A smart quick man at anything; ’Twas hard to put him wrong …

One day they brought him from the mine … (The big salt tears will fall) …

‘’Twas long ago, God rest his soul!’ Poor Granny ‘minds it all.’

The first dark days of widowhood, the weary days and slow,

The grim, disheartening, uphill fight, then Granny lived to know.

‘The childer,’ ah! they grew and grew—sound, rosycheeked, and tall:

‘The childer’ still they are to her. Old Granny ‘minds them all.’

How well she loved her little brood! Oh, Granny’s heart was brave!

She gave to them her love and faith—all that the good God gave.

They change not with the changing years: as babies just the same

She feels for them—though some, alas, have brought her grief and shame.

The big world called them here and there, and many a mile away:

They cannot come—she cannot go—the darkness haunts the day;

And I, no flesh and blood of hers, sit here while shadows fall—

I sit and listen—Granny talks; for Granny ‘minds them all.’

Just fancy Granny Sullivan at seventeen or so,

In all the floating finery that women love to show;

And oh! It is a merry dance: the fiddler’s flushed with wine

And Granny’s partner brave and gay, and Granny’s eyes ashine …2

’Tis time to pause, for pause we must: we only have our day:

Yes: by and by our dance will die, our fiddlers cease to p

lay;

And we shall seek some quiet place where great grey shadows fall,

And sit and wait as Granny waits—we’ll sit and ‘mind them all.’

The Bookfellow, 1907

29

Old Man Platypus

Banjo Paterson

Far from the trouble and toil of town,

Where the reed beds sweep and shiver,

Look at a fragment of velvet brown—

Old Man Platypus drifting down,

Drifting along the river.

And he plays and dives in the river bends

In a style that is most elusive;

With few relations and fewer friends,

For Old Man Platypus descends

From a family most exclusive.

He shares his burrow beneath the bank

With his wife and his son and daughter

At the roots of the reeds and the grasses rank;

And the bubbles show where our hero sank

To its entrance under water.

Safe in their burrow below the falls

They live in a world of wonder,

Where no one visits and no one calls,

They sleep like little brown billiard balls

With their beaks tucked neatly under.

And he talks in a deep unfriendly growl

As he goes on his journey lonely;

For he’s no relation to fish nor fowl,

Nor to bird nor beast, nor to horned owl;

In fact, he’s the one and only!

The Animals Noah Forgot, 1933

30

60 Classic Australian Poems for Children

60 Classic Australian Poems for Children