60 Classic Australian Poems for Children Read online

Page 7

As I came down to Mass.’

‘If rain don’t come this month,’ said Dan,

And cleared his throat to speak—

‘We’ll all be rooned,’ said Hanrahan,

‘If rain don’t come this week.’

A heavy silence seemed to steal

On all at this remark;

And each man squatted on his heel,

And chewed a piece of bark.

‘We want a inch of rain, we do,’

O’Neil observed at last;

But Croke ‘maintained’ we wanted two

To put the danger past.

‘If we don’t get three inches, man,

Or four to break this drought,

We’ll all be rooned,’ said Hanrahan,

‘Before the year is out.’

In God’s good time down came the rain;

And all the afternoon

On iron roof and window-pane

It drummed a homely tune.

And through the night it pattered still,

And lightsome, gladsome elves

On dripping spout and window-sill

Kept talking to themselves.

It pelted, pelted all day long,

A-singing at its work,

Till every heart took up the song

Way out to Back-o’-Bourke.

And every creek a banker ran,

And dams filled overtop;

‘We’ll all be rooned,’ said Hanrahan,

‘If this rain doesn’t stop.’

And stop it did, in God’s good time:

And spring came in to fold

A mantle o’er the hills sublime

Of green and pink and gold.

And days went by on dancing feet,

With harvest-hopes immense,

And laughing eyes beheld the wheat

Nid-nodding o’er the fence.

And, oh, the smiles on every face,

As happy lad and lass

Through grass knee-deep on Casey’s place

Went riding down to Mass.

While round the church in clothes genteel

Discoursed the men of mark,

And each man squatted on his heel,

And chewed his piece of bark,

‘There’ll be bush-fires for sure, me man,

There will, without a doubt;

We’ll all be rooned,’ said Hanrahan,

‘Before the year is out.’

Around the Boree Log and other verses, 1922

* * *

In 1911 PJ Hartigan (John O’Brien) purchased his first motor car. He was one of the first curates in NSW to own one. He loved cars. During his life he owned many!

Father O’Brien was once asked by the Albury parish priest to drive him to administer the last rites to a man called Jack Riley.

After receiving the last rites, Father O’Brien recited ‘The Man from Snowy River’ not knowing that Riley had told Banjo Paterson about one of his rides, the ride that became Paterson’s famous poem.

* * *

41

Santa Claus in the Bush

Banjo Paterson

It chanced out back at the Christmas time,

When the wheat was ripe and tall,

A stranger rode to the farmer’s gate—

A sturdy man, and a small.

‘Run down, run down, my little son Jack,

And bid the stranger stay;

And we’ll hae a crack for the “Auld Lang Syne,”

For to-morrow is Christmas Day.’

‘Nay now, nay now,’ said the dour gude wife,

‘But ye should let him be;

He’s maybe only a drover chap

From the land o’ the Darling Pea.

‘Wi’ a drover’s tales, and a drover’s thirst

To swiggle the hail night through;

Or he’s maybe a life assurance carle,

To talk ye black and blue.’

‘Gude wife, he’s never a drover chap,

For their swags are neat and thin;

And he’s never a life assurance carle,

Wi’ the brick-dust burnt in his skin.

‘Gude wife, gude wife, be not so dour,

For the wheat stands ripe and tall,

And we shore wi’ a seven-pound fleece this year,

Ewes and weaners and all.

‘There is grass to spare, and the stock are fat.

When the whiles are gaunt and thin,

And we owe a tithe to the travelling poor,

So we must ask him in.

‘You can set him a chair to the table side,

And give him a bite to eat;

An omelette made of a new laid egg,

Or a tasty bit of meat.’

‘But the native cats have taken the fowls,

They have na’ left a leg;

And he’ll get no omelette at all

Till the emu lays an egg!’

‘Run down, run down, my little son, Jack,

To where the emus bide,

Ye shall find the old hen on the nest,

While the old cock sits beside.

‘But speak them fair, and speak them soft,

Lest they kick ye a fearsome jolt.

Ye can gi’ them a feed of thae half-inch nails

Or a rusty carriage bolt.’

So little son Jack ran blithely down

With the rusty nails in hand,

Till he came where the emus fluffed and scratched,

By their nest in the open sand.

And there he has gathered the new-laid egg,

Would feed three men or four,

And the emus came for the half-inch nails

Right up to the settler’s door.

‘A waste o’ food,’ said the dour gude wife,

As she took the egg, wi’ a frown,

‘But he gets no meat, unless ye run

A paddy-melon down.’

‘Gae oot, gae oot, my little son Jack,

Wi’ your twa-three doggies small;

Gin ye come not back wi’ a paddy-melon,

Then come not back at all.’

So little son Jack he raced and he ran,

And he was bare o’ the feet,

And soon he captured the paddy-melon,

Was gorged wi’ the stolen wheat.

‘Sit down, sit down, my bonny wee man,

To the best that the house can do—

An omelette made of the Emu egg

And a Paddy-melon stew.’

‘’Tis well, ’tis well,’ said the bonny wee man;

‘I have eaten the wide world’s meat,

But the food that is given wi’ right good will

Is the sweetest food to eat.

‘But the night draws on to the Christmas Day

And I must rise and go,

For I have a mighty way to ride

To the land of the Esquimaux.

‘And it’s there I must load my sledges up,

With the reindeers four-in-hand,

That go to the north, south, east, and west,

To every Christian land.’

‘Tae the Esquimaux,’ said the dour good wife,

‘Ye suit my husband well!

For when he gets up on his journey horse

He’s a bit of a liar himsel’.’

Then out with a laugh went the bonny wee man

To his old horse grazing nigh,

And away like a meteor flash they went

Far off to the northern sky.

When the children woke on the Christmas morn

They chattered with might and main—

Wi’ a sword and gun for little son Jack,

And a braw new doll had Jane,

And a packet o’ nails had the twa Emus;

But the dour gude wife gat nane.

Australian Town and Country Journal, 1906

42

The Shearer’s Wife

Louis Esson

Th

e dark—but drudgin’s never done;

Now after tea inside the door

I patch an’ darn from set o’ sun,

Till hands git stiff and eyes grow sore,

While Dick’s outback.

And times I lie awake o’ nights

An’ watch the moon throw tricksy lights

An’ shadows skeer with creepy sights

Out in the ranges black.

Before the glare o’ dawn I rise

To milk the sleepy cows, an’ feed

The chooky-hens I dearly prize:

I set the bunny traps, then knead

The weekly bread.

There’s hay to stook, an’ spuds to hoe,

An’ ferns to cut in the scrub below,

An’ I lay out palin’s row on row

To make a new cow-shed.

The poorness of this Savage Bush

Has crushed us since we came from town,

(To-night I’m dreamin’ through the hush:

My eyes are bright, my hair’s still brown,

And I’m Young Lil.

‘We’ll have a farm,’ Dick used to say,

‘Where we’ll be happy all the day,’

But now I’m wrinkled, worn, an’ grey,

And Dick’s a shearer still.)

Blurred runs the track whereon he comes,

And tired am I with labour sore;

Tired o’ the bush, an’ cows, an’ gums,

Tired—an’ I want to think no more.

What tales he tells

The moon is lonesome in the sky,

The bush is lone, and lonesome I

But Stare as the red dust clouds whirl by,

And start at the cattle bells.

The Bulletin, 1907

43

A Snake Yarn

WT Goodge

‘You talk of snakes,’ said Jack the Rat,

‘But blow me, one hot summer,

I seen a thing that knocked me flat—

Fourteen foot long or more than that.

It was a reg’lar hummer!

Lay right along a sort of bog,

Just like a log!

‘The ugly thing was lyin’ there

And not a sign o’ movin’,

Give any man a nasty scare;

Seen nothin’ like it anywhere

Since I first started drovin’.

And yet it didn’t scare my dog.

Looked like a log!

‘I had to cross that bog, yer see,

And bluey I was humpin’;

But wonderin’ what that thing could be

A-lyin’ there in front o’ me

I didn’t feel like jumpin’.

Yet, though I shivered like a frog,

It seemed a log!

‘I takes a leap and lands right on

The back of that there whopper!’

He stopped. We waited. Then Big Mac

Remarked: ‘Well, then, what happened, Jack?’

‘Not much,’ said Jack, and drained his grog.

‘It was a log!’

The Bulletin, 1899

44

Song of the Artesian Waters

Banjo Paterson

Now the stock have started dying, for the Lord has sent a drought;

But we’re sick of prayers and Providence—we’re going to do without;

With the derricks up above us and the solid earth below,

We are waiting at the lever for the word to let her go.

Sinking down, deeper down;

Oh, we’ll sink it deeper down.

As the drill is plugging downward at a thousand feet of level,

If the Lord won’t send us water, oh, we’ll get it from the devil;

Yes, we’ll get it from the devil deeper down.

Now, our engine’s built in Glasgow by a very canny Scot,

And he marked it twenty horse-power, but he don’t know what is what.

When Canadian Bill is firing with the sun-dried gidgee logs,

She can equal thirty horses and a score or so of dogs.

Sinking down, deeper down,

Oh, we’re going deeper down.

If we fail to get the water then it’s ruin to the squatter,

For the drought is on the station and the weather’s growing hotter;

But we’re bound to get the water deeper down.

But the shaft has started caving and the sinking’s very slow,

And the yellow rods are bending in the water down below,

And the tubes are always jamming and they can’t be made to shift

Till we nearly burst the engine with a forty horse-power lift.

Sinking down, deeper down,

Oh, we’re going deeper down.

Though the shaft is always caving, and the tubes are always jamming,

Yet we’ll fight our way to water while the stubborn drill is ramming—

While the stubborn drill is ramming deeper down.

But there’s no artesian water, though we’ve passed three thousand feet,

And the contract price is growing and the boss is nearly beat.

But it must be down beneath us, and it’s down we’ve got to go,

Though she’s bumping on the solid rock four thousand feet below.

Sinking down, deeper down;

Oh, we’re going deeper down,

And it’s time they heard us knocking on the roof of

Satan’s dwellin’;

But we’ll get artesian water if we cave the roof of hell in—

Oh! we’ll get artesian water deeper down.

But it’s hark! the whistle’s blowing with a wild, exultant blast,

And the boys are madly cheering, for they’ve struck the flow at last,

And it’s rushing up the tubing from four thousand feet below,

Till it spouts above the casing in a million-gallon flow.

And it’s down, deeper down—

Oh, it comes from deeper down;

It is flowing, ever flowing, in a free, unstinted measure

From the silent hidden places where the old earth hides her treasure—

Where the old earth hides her treasure deeper down.

And it’s clear away the timber, and it’s let the water run:

How it glimmers in the shadow, how it flashes in the sun!

By the silent belts of timber, by the miles of blazing plain

It is bringing hope and comfort to the thirsty land again.

Flowing down, further down;

It is flowing further down

To the tortured thirsty cattle, bringing gladness in its going;

Through the droughty days of summer it is flowing, ever flowing—

It is flowing, ever flowing, further down.

The Bulletin (Christmas edition), 1899

45

The Swagman

CJ Dennis

Oh, he was old and he was spare;

His bushy whiskers and his hair

Were all fussed up and very grey.

He said he’d come a long, long way

And had a long, long way to go.

Each boot was broken at the toe,

And he’d a swag upon his back.

His billy-can, as black as black,

Was just the thing for making tea

At picnics, so it seemed to me.

* * *

A Book for Kids was first published in 1921 and then republished as Roundabout in 1935. This poem was possibly CJ Dennis’s favourite.

* * *

’Twas hard to earn a bite of bread,

He told me. Then he shook his head,

And all the little corks that hung

Around his hat-brim danced and swung

And bobbed about his face; and when

I laughed he made them dance again.

He said they were for keeping flies—

‘The pesky varmints’—from his eyes.

He called me ‘Codger’ … ‘Now you

see

The best days of your life,’ said he.

‘But days will come to bend your back,

And, when they come, keep off the track.

Keep off, young codger, if you can.’

He seemed a funny sort of man.

He told me that he wanted work,

But jobs were scarce this side of Bourke,

And he supposed he’d have to go

Another fifty mile or so.

‘Nigh all my life the track I’ve walked,’

He said. I liked the way he talked.

And oh, the places he had seen!

I don’t know where he had not been—

On every road, in every town,

All through the country, up and down.

‘Young codger, shun the track,’ he said.

And put his hand upon my head.

I noticed, then, that his old eyes

Were very blue and very wise.

‘Ay, once I was a little lad,’

He said, and seemed to grow quite sad.

I sometimes think: When I’m a man,

I’ll get a good black billy-can

And hang some corks around my hat,

And lead a jolly life like that.

A Book for Kids, 1921

46

Tangmalangaloo

PJ Hartigan (John O’Brien)

The bishop sat in lordly state and purple cap sublime,

And galvanized the old bush church at Confirmation time.

And all the kids were mustered up from fifty miles around,

With Sunday clothes, and staring eyes, and ignorance profound.

Now was it fate, or was it grace, whereby they yarded too

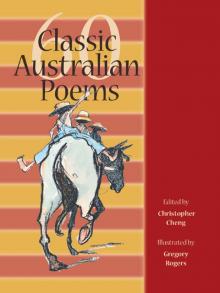

60 Classic Australian Poems for Children

60 Classic Australian Poems for Children