60 Classic Australian Poems for Children Read online

Page 4

Hip ……. Hooray!

A Book for Kids, 1921

19

How M’Dougal Topped the Score

Thomas E Spencer

A peaceful spot is Piper’s Flat. The folk that live around—

They keep themselves by keeping sheep and turning up the ground.

But the climate is erratic; and the consequences are

The struggle with the elements is everlasting war.

We plough, and sow, and harrow—then sit down and pray for rain;

And then we get all flooded out and have to start again.

But the folk are now rejoicing as they ne’er rejoiced before,

For we’ve played Molongo cricket, and M’Dougal topped the score!

Molongo had a head on it, and challenged us to play

A single-innings match for lunch—the losing team to pay.

We were not great guns at cricket, but we couldn’t well say No,

So we all began to practise, and we let the reaping go.

We scoured the Flat for ten miles round to muster up our men,

But when the list was totalled we could only number ten.

Then up spoke big Tim Brady: he was always slow to speak,

And he said—‘What price M’Dougal, who lives down at Cooper’s Creek?’

So we sent for old M’Dougal, and he stated in reply

That ‘he’d never played at cricket, but he’d half a mind to try.

He couldn’t come to practice—he was getting in his hay,

But he guessed he’d show the beggars from Molongo how to play.’

Now, M’Dougal was a Scotchman, and a canny one at that,

So he started in to practise with a paling for a bat.

He got Mrs. Mac. to bowl him, but she couldn’t run at all,

So he trained his sheep-dog, Pincher, how to scout and fetch the ball.

Now, Pincher was no puppy; he was old, and worn, and grey;

But he understood M’Dougal, and—accustomed to obey—

When M’Dougal cried out ‘Fetch it!’ he would fetch it, in a trice;

But, until the word was ‘Drop it!’ he would grip it like a vyce.

And each succeeding night they played until the light grew dim;

Sometimes M’Dougal struck the ball—sometimes the ball struck him!

Each time he struck, the ball would plough a furrow in the ground,

And when he missed, the impetus would turn him three times round.

The fatal day at length arrived—the day that was to see

Molongo bite the dust, or Piper’s Flat knocked up a tree!

Molongo’s captain won the toss, and sent his men to bat,

And they gave some leather-hunting to the men of Piper’s Flat.

When the ball sped where M’Dougal stood, firm planted in his track,

He shut his eyes, and turned him round, and stopped it—with his back!

The highest score was twenty-two, the total sixty-six,

When Brady sent a yorker down that scattered Johnson’s sticks.

Then Piper’s Flat went in to bat, for glory and renown,

But, like the grass before the scythe, our wickets tumbled down.

‘Nine wickets down for seventeen, with fifty more to win!’

Our captain heaved a heavy sigh, and sent M’Dougal in.

‘Ten pounds to one you lose it!’ cried a barracker from town;

But M’Dougal said ‘I’ll tak’ it mon!’ and planked the money down.

Then he girded up his moleskins in a self-reliant style,

Threw off his hat and boots, and faced the bowler with a smile.

He held the bat the wrong side out, and Johnson with a grin,

Stepped lightly to the bowling crease, and sent a ‘wobbler’ in;

M’Dougal spooned it softly back, and Johnson waited there,

But M’Dougal, cryin’ ‘Fetch it!’ started running like a hare.

Molongo shouted ‘Victory! He’s out as sure as eggs.’

When Pincher started through the crowd, and ran through Johnson’s legs.

He seized the ball like lightning; then he ran behind a log,

And M’Dougal kept on running, while Molongo chased the dog.

They chased him up, they chased him down, they chased him round, and then

He darted through a slip-rail as the scorer shouted ‘Ten!’

M’Dougal puffed; Molongo swore; excitement was intense;

As the scorer marked down twenty, Pincher cleared a barbedwire fence.

‘Let us head him!’ shrieked Molongo. ‘Brain the mongrel with a bat!’

‘Run it out! Good old McDougal!’ yelled the men of Piper’s Flat.

And McDougal kept on jogging, and then Pincher doubled back,

And the scorer counted ‘Forty’ as they raced across the track.

McDougal’s legs were going fast, Molongo’s breath was gone—

But still Molongo chased the dog—McDougal struggled on.

When the scorer shouted ‘Fifty!’ then they knew the chase would cease;

And McDougal gasped out ‘Drop it!’ as he dropped within his crease.

Then Pincher dropped the ball, and as instinctively he knew

Discretion was the wiser plan, he disappeared from view.

And as Molongo’s beaten men exhausted lay around

We raised McDougal shoulder-high, and bore him from the ground.

We bore him to M’Ginniss’s, where lunch was ready laid,

And filled him up with whisky-punch, for which Molongo paid.

We drank his health in bumpers, and we cheered him three times three,

And when Molongo got its breath, Molongo joined the spree.

And the critics say they never saw a cricket match like that,

When M’Dougal broke the record in the game at Piper’s Flat.

And the folks were jubilating as they never were before;

For we played Molongo cricket, and M’Dougal topped the score!

The Bulletin, 1898

Note the change to McDougal part way through.

20

The Last of His Tribe

Henry Kendall

He crouches, and buries his face on his knees,

And hides in the dark of his hair;

For he cannot look up to the storm-smitten trees,

Or think of the loneliness there—

Of the loss and the loneliness there.

The wallaroos grope through the tufts of the grass,

And turn to their coverts for fear;

But he sits in the ashes and lets them pass

Where the boomerangs sleep with the spear—

With the nullah, the sling and the spear.

Uloola, behold him! The thunder that breaks

On the tops of the rocks with the rain,

And the wind which drives up with the salt of the lakes,

Have made him a hunter again—

A hunter and fisher again.

For his eyes have been full with a smouldering thought;

But he dreams of the hunts of yore,

And of foes that he sought, and of fights that he fought

With those who will battle no more—

Who will go to the battle no more.

It is well that the water which tumbles and fills,

Goes moaning and moaning along;

For an echo rolls out from the sides of the hills,

And he starts at a wonderful song—

At the sound of a wonderful song.

And he sees, through the rents of the scattering fogs,

The corroboree warlike and grim,

And the lubra who sat by the fire on the logs,

To watch, like a mourner, for him—

Like a mother and mourner for him.

Will he go in his sleep from these desolate lands,

Like a chief, to the rest of his race,

With the honey-voiced woman who

&nb

sp; beckons and stands,

And gleams like a dream in

his face—

Like a marvellous dream in

his face?

Poems of Henry Kendall, 1886

21

The Lights of Cobb and Co.

Henry Lawson

Fire-lighted, on the table a meal for sleepy men,

A lantern in the stable, a jingle now and then;

The mail-coach looming darkly by light of moon and star,

The growl of sleepy voices—a candle in the bar;

A stumble in the passage of folk with wits abroad;

A swear-word from a bedroom—the shout of ‘All aboard!’

‘Tchk-tchk! Git-up!’ ‘Hold fast, there!’ and down the range we go;

Five hundred miles of scattered camps will watch for Cobb and Co.

Old coaching towns already ‘decaying for their sins’

Uncounted Half-Way Houses, and scores of ‘Ten Mile Inns’;

The riders from the stations by lonely granite peaks;

The black-boy for the shepherds on sheep and cattle creeks;

The roaring camps of Gulgong, and many a ‘Digger’s Rest’;

The diggers on the Lachlan; the huts of Farthest West;

Some twenty thousand exiles who sailed for weal or woe;

The bravest hearts of twenty lands will wait for Cobb and Co.

The morning star has vanished, the frost and fog are gone,

In one of those grand mornings which but on mountains dawn;

A flask of friendly whisky—each other’s hopes we share—

And throw our top-coats open to drink the mountain air.

The roads are rare to travel, and life seems all complete;

The grind of wheels on gravel, the trot of horses’ feet,

The trot, trot, trot and canter, as down the spur we go—

The green sweeps to horizons blue that call for Cobb and Co.

We take a bright girl actress through western dust and damps,

To bear the home-world message, and sing for sinful camps,

To wake the hearts and break them, wild hearts that hope and ache—

(Ah! when she thinks of those days her own must nearly break!)

Five miles this side the gold-field, a loud, triumphant shout:

Five hundred cheering diggers have snatched the horses out,

With ‘Auld Lang Syne’ in chorus through roaring camps they go—

That cheer for her, and cheer for Home, and cheer for Cobb and Co.

Three lamps above the ridges and gorges dark and deep,

A flash on sandstone cuttings where sheer the sidings sweep,

A flash on shrouded waggons, on water ghastly white;

Weird bush and scattered remnants of ‘rushes’ in the night

Across the swollen river a flash beyond the ford:

‘Ride hard to warn the driver! He’s drunk or mad, good Lord!’

But on the bank to westward a broad, triumphant glow—

A hundred miles shall see to-night the lights of Cobb and Co.!

Swift scramble up the siding where teams climb inch by inch;

Pause, bird-like, on the summit—then breakneck down the ‘pinch’!

Past haunted half-way houses—where convicts made the bricks—

Scrub-yards and new bark shanties, we dash with five and six—

By clear, ridge-country rivers, and gaps where tracks run high,

Where waits the lonely horseman, cut clear against the sky;

Through stringy-bark and blue-gum, and box and pine we go;

New camps are stretching ’cross the plains the routes of Cobb and Co.

Throw down the reins, old driver—there’s no one left to shout;

The ruined inn’s survivor must take the horses out.

A poor old coach hereafter!—we’re lost to all such things—

No bursts of songs or laughter shall shake your leathern springs.

When creeping in unnoticed by railway sidings drear,

Or left in yards for lumber, decaying with the year—

Oh, who’ll think how in those days when distant fields

were broad

You raced across the Lachlan side with twenty-five on board.

Not all the ships that sail away since Roaring Days are done—

Not all the boats that steam from port, nor all the trains that run,

Shall take such hopes and loyal hearts—for men shall never know

Such days as when the Royal Mail was run by Cobb and Co.

The ‘greyhounds’ race across the sea, the ‘special’ cleaves the haze,

But these seem dull and slow compared with bygone Roaring Days!

The eyes that watched are dim with age, and souls are weak and slow,

The hearts are dust or hardened now that broke for Cobb and Co.

The Bulletin (Christmas edition), 1897

22

The Man from Ironbark

Banjo Paterson

It was the man from Ironbark who struck the Sydney town,

He wandered over street and park he wandered up and down.

He loitered here, he loitered there, till he was like to drop

Until at last in sheer despair he sought a barber’s shop.

‘’Ere! shave my hair and whiskers off, I’ll be a man of mark,

I’ll go and do the Sydney toff up home in Ironbark.’

The barber man was small and flash, as barbers mostly are,

He wore a strike-your-fancy sash, he smoked a huge cigar:

He was a humorist of note and keen at repartee,

He laid the odds and kept a ‘tote’ whatever that may be,

And when he saw our friend arrive he whispered ‘here’s a lark!

Just watch me catch him all alive, this man from Ironbark.’

There were some gilded youths that sat along the barber’s wall,

Their eyes were dull, their heads were flat, they had no brains at all;

To them the barber passed the wink, his dexter eyelid shut,

‘I’ll make this bloomin’ yokel think his bloomin’ throat is cut.’

And as he soaped and rubbed it in he made a rude remark:

‘I s’pose the flats is pretty green up there in Ironbark.’

A grunt was all reply he got; he shaved the bushman’s chin,

Then made the water boiling hot and dipped the razor in.

He raised his hand, his brow grew black, he paused awhile to gloat,

Then slashed the red-hot razor-back across his victim’s throat;

Upon the newly shaven skin it made a livid mark—

No doubt it fairly took him in the man from Ironbark.

He fetched a wild up-country yell the dead might wake to hear,

And though his throat, he knew full well was cut from ear to ear,

He struggled gamely to his feet, and faced the murd’rous foe

‘You’ve done for me! you dog, I’m beat! One hit before I go!

I only wish I had a knife, you blessed murdering shark!

But you’ll remember all your life, the man from Ironbark.’

He lifted up his hairy paw, with one tremendous clout

He landed on the barber’s jaw, and knocked the barber out.

He set to work with tooth and nail, he made the place a wreck;

He grabbed the nearest gilded youth and tried to break his neck.

And all the while his throat he held to save his vital spark,

And ‘Murder! Bloody Murder!’ yelled the man from Ironbark.

A peeler man who heard the din came in to see the show,

He tried to run the bushman in, but he refused to go.

And when at last the barber spoke, and said, ‘’twas all in fun,

’Twas just a little harmless joke, a trifle overdone.’

‘A joke!’ he cried, ‘by George, that’s fine, a lively sort of lark;

I’d like to catch that murdering swi

ne some night in Ironbark.’

And now while round the shearing floor the list’ning shearers gape,

He tells the story o’er and o’er and brags of his escape.

‘Them barber chaps what keeps a tote, by George, I’ve had enough,

One tried to cut my bloomin’ throat, but thank the Lord it’s tough!’

And whether he’s believed or no, there’s one thing to remark,

That flowing beards are all the go way up in Ironbark.

The Bulletin (Christmas edition), 1892

23

The Man from Snowy River

Banjo Paterson

There was movement at the station, for the word had passed around

That the colt from old Regret had got away

And had joined the wild bush horses—he was worth a thousand pound—

So all the cracks had gathered to the fray.

All the tried and noted riders from the stations near and far

Had mustered at the homestead over-night,

For the bushmen love hard-riding where the fleet wild horses are,

And the stockhorse snuffs the battle with delight.

There was Harrison, who made his pile when Pardon won the Cup,

The old man with his hair as white as snow,

But few could ride beside him when his blood was fairly up—

He would go wherever horse and man could go.

And Clancy of the Overflow came down to lend a hand—

No better horseman ever held the reins;

For never horse could throw him while the saddle-girths would stand,

He learnt to ride while droving on the plains.

And one was there, a stripling on a small and graceful beast;

He was something like a racehorse undersized,

With a touch of Timor pony, three parts thoroughbred at least,

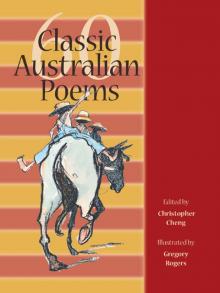

60 Classic Australian Poems for Children

60 Classic Australian Poems for Children